Petra – Secrets of Jordan’s Lost City

Sandstone stacks the size of giant handfuls of sun-baked clay loom over the arid valley of Wadi Musa. However, even in this parched landscape, there are places where the sun does not shine. The Siq is permanently cast in shadow by 200m-high walls, as if the long, narrow canyon passes through the mountain’s dark heart. At dawn, it is completely silent, with not even a bird’s chirrup to accompany solitary footsteps along its patchwork floor of rock and sand.

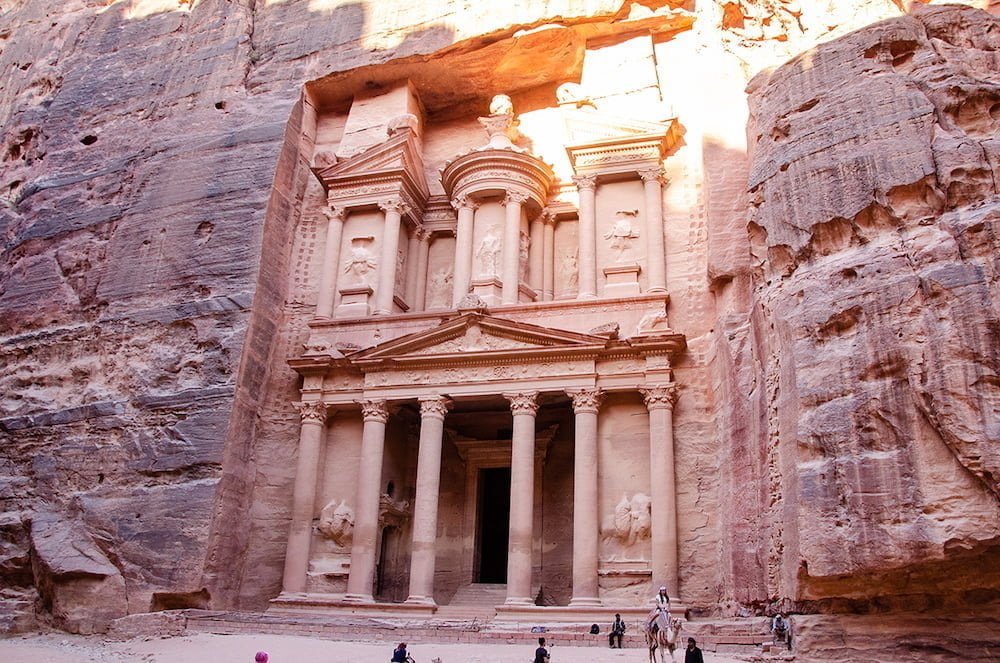

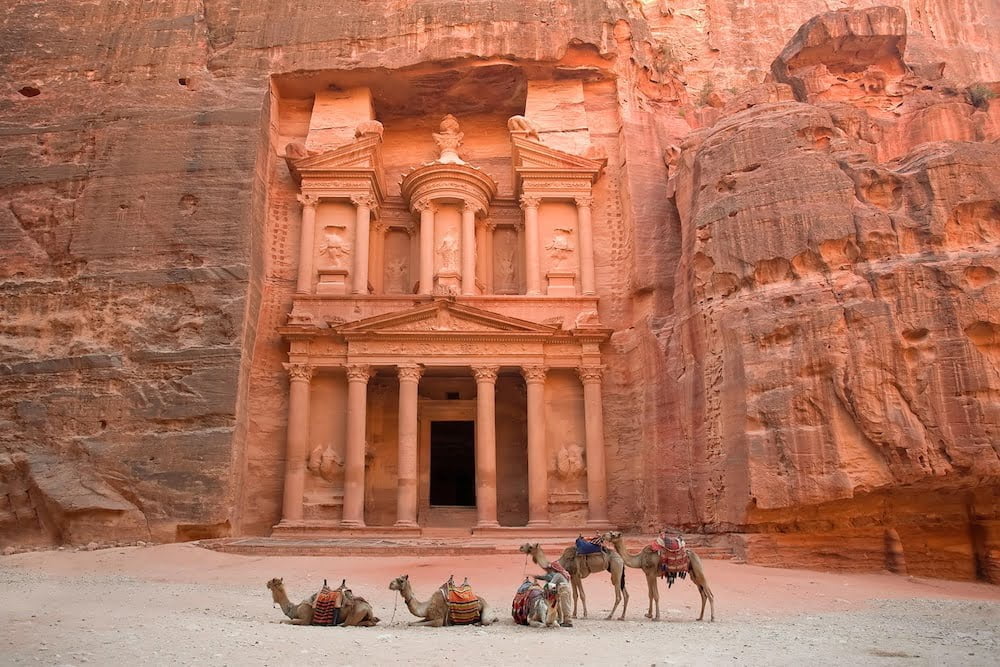

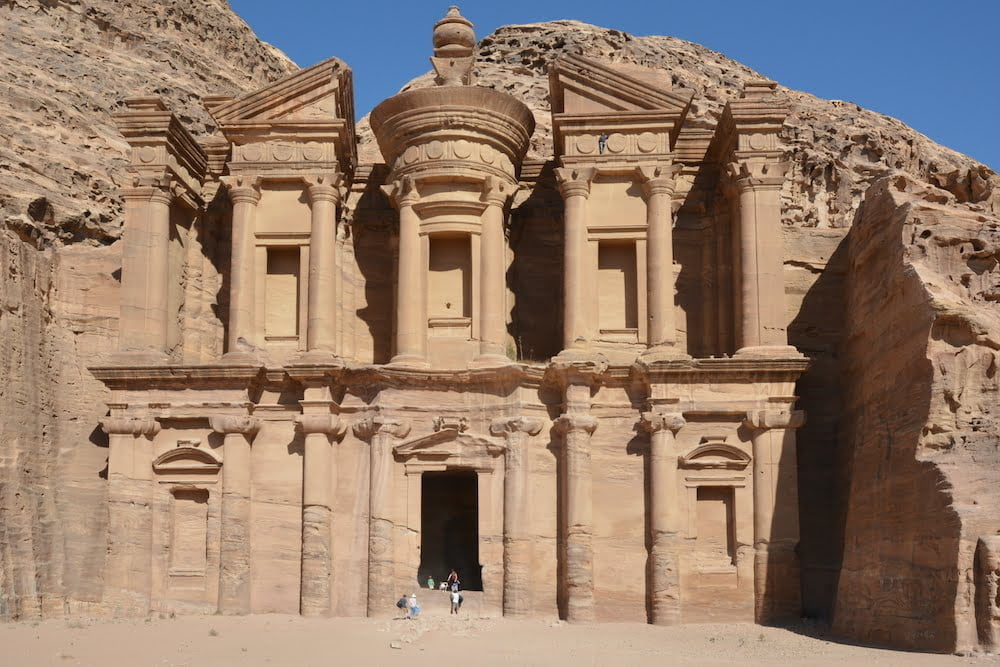

Petra makes its presence known through a lightning-bolt-shaped opening. The Treasury’s vast facade, precisely carved into the soft sandstone, towers over the young Bedouin men, camels, and stray cats gathered at its base.

Petra’s Rediscovery

‘It is one of the most elegant antiquity remains existing,’ wrote Swiss explorer Jean Louis Burckhardt in his diary in 1812. Burckhardt was the first outsider to cross Petra’s threshold in more than 600 years; hidden by natural fortifications, the city had remained unknown to the West since the Crusades. Though local Bedouin tribes were aware of its existence, they were hesitant to reveal it for fear of attracting treasure hunters.

Petra had been anything but anonymous in its heyday, around the time of Christ. It was the center of a kingdom four times the size of modern Jordan, with 30,000 people surviving in this desert landscape thanks to a complex water management system. The Nabataeans, a once-nomadic Arab tribe who used their knowledge of the desert to amass vast wealth in the caravan trade, most notably that of frankincense and myrrh, were at the helm.

The Treasury’s grand edifice was a declaration of wealth, sending a powerful message to weary traders emerging from the Siq, but it was essentially an empty shell. The misnomer ‘the Treasury’ came from the belief that the urn carved into the center of the second tier contained hidden gold. It was built as a tomb for a Nabataean king. The vessel is riddled with bullet holes, evidence of previous attempts to locate the mythical bounty.

But the treasure Burckhardt sought was intellectual rather than mercantile; he relocated to Syria’s Aleppo, learned Arabic, converted to Islam, and assumed the name Sheikh Ibrahim bin Abdullah. The 27-year-ethnicity old’s was further obscured by a deep tan and full beard, and he became a master of disguise, adopting local customs and testing his alias among the Bedouin.

Burckhardt’s mysterious strategy

When he heard of ruins hidden among the mountains of Wadi Musa while traveling south to Cairo, he developed a ruse: ‘I pretended to have made a vow to have slaughtered a goat in honour of Haroun (Aaron), whose tomb I knew was situated in the extremity of the valley, and by this stratagem I thought that I should have the means of seeing the valley on the way to the tomb,’ he wrote.

His plan worked. When he first arrived in the city, he was barely able to hide his awe from his tour guide. Burckhardt was taken aback by the sight of countless tombs and the great amphitheatre carved into the rock as the two traveled deeper into the valley. He couldn’t help but scramble up to investigate. These caves were bare then, as they are now, except for the veins of color striped through the rock like natural wallpaper. Burckhardt was hurried to the city’s parched core, the Colonnaded Street, and the temple of Qasr Al Bint, after surprising his guide with his incursions. His attempt to explore the latter’s ruins was the final straw. ‘I see now that you are an infidel!’ exclaimed his guide. Burckhardt refused to go any further, fearing that further anguish would lead to the discovery of his most prized possession, his diary.

Away from the tourist areas of Petra

Few tourists venture beyond Petra’s main sites, and with each step away from the city, we become more isolated – until there are no other people in sight. If the stretch from the Treasury to Qasr Al Bint is Petra’s major road, these outlying hills are its suburbs.

Though the weathered rockface is still dotted with ancient dwellings and sepulchres, many are more modest in nature. Some grander efforts remain unfinished – remnants of an urban sprawl that came to a halt – and it is possible to see the Nabataean technique of carving from top to bottom with these edifices. As we ascend further into the hills, we come across what must be one of the last Bedouin family homes. Its dark entrance-way has been replaced with a solid door, and there is a garden of plants and fruit trees. We arrive at Haroun’s Terrace with the sun directly overhead. A small white mosque can be seen from here. This is Jebel Haroun, which is thought to be biblical Mount Hor and is where Moses’ brother Aaron (Haroun to Muslims) is buried. It is a sacred place for both Christians and Muslims.

Cultural formation

Petra’s style was a mash-up of influences absorbed along their trade routes: Egyptian, Assyrian, Hellenistic, Mesopotamian, and Roman imagery infused with their own creative flourishes. The scale of their ambition is most visible at Petra’s largest monument, the Monastery, which is carved deep into the mountainside. It’s easy to picture the hours of chiselling and carving that went into making it. Even getting to the Monastery requires effort: it is located at the top of an 800-step rock-cut path that follows the path taken by the faithful when this was a place of worship.

The name of the Monastery is deceptive; it was probably built as a tomb in the third century BC and later converted to a temple. Crosses etched into the internal walls indicate that it was used as a church by the Byzantines – Petra is a place that has witnessed the rise and fall of one civilisation after another. The fictional doctor’s quest for the Holy Grail led him to Petra in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Burckhardt never made it all the way to the Monastery. Despite the fact that a letter back to his colleagues reporting his discovery sparked wild excitement, he never got to enjoy his fame. He spent the rest of his life as Sheikh Ibrahim bin Abdullah, traveling throughout the Middle East and Africa, before dying of dysentery at the age of 32 in 1817. Countless others – explorers, scholars, and the simply curious – followed in his footsteps over the next two centuries, but Petra remains a place full of untold secrets.